A few weeks ago, I conducted a strange experiment.

I locked my smartphone in a drawer, disabled all notifications on my laptop, and committed to working on a single project for three uninterrupted hours. No email checks. No social media "quick breaks." No context switching to other tasks.

Just three hours of sustained, focused effort on one complex problem.

The results were both alarming and illuminating. The first 30 minutes were excruciating. My brain, so accustomed to constant stimulation, rebelled against the constraint. I found myself inventing reasons to check my phone or hop to another task. My mind felt like a toddler having a tantrum.

But something shifted around the 45-minute mark. The resistance began to dissolve. By hour two, I had entered a state of immersion I hadn't experienced in years. And by the end of hour three, I had made more meaningful progress on this project than in the previous two weeks of fragmented work.

This experience left me with a troubling question: If three hours of deep focus yields such dramatically different results, why is it so rare in my daily life?

The Lost Art of Deep Work

In his book "Deep Work," computer science professor Cal Newport defines deep work as "professional activities performed in a state of distraction-free concentration that push your cognitive capabilities to their limit."

This is the kind of work that creates new value, improves skills, and produces insights that shallow, fragmented attention cannot. It's the difference between skating on the surface of multiple tasks and diving deeply into one important problem.

The ability to perform deep work is becoming increasingly rare at exactly the same time it is becoming increasingly valuable in our economy. Deep work is like a superpower in the knowledge economy. It enables you to quickly master hard things and produce at an elite level in terms of both quality and speed.

The Attention Economy's Hidden Cost

The most unsettling realization from my experiment wasn't how productive those three hours were—it was recognizing how unusual they had become in my life.

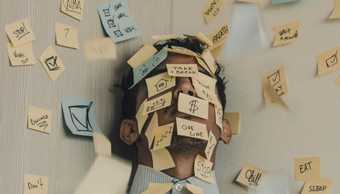

We now live in what's called the "attention economy," where the most valuable commodity is human attention. Tech companies employ thousands of engineers whose job is to fragment your focus and harvest your attention in small chunks to sell to advertisers.

Their efforts have been wildly successful. The average person now checks their phone 96 times per day—once every 10 minutes. The average worker checks email 74 times and switches tasks every 3 minutes. Our brains are being systematically trained away from deep focus.

The costs of this cognitive fragmentation go far beyond productivity:

-

Complex problem solving requires deep focus. Many of society's most important challenges cannot be addressed with fractured attention.

-

Meaningful human connection suffers. When was the last time you had a deep conversation without devices present?

-

We lose the ability to be alone with our thoughts. Studies show modern humans would rather receive mild electric shocks than sit quietly with their own thoughts for 15 minutes.

-

Shallow work begets shallow thinking. As philosopher Matthew Crawford notes, "Attention is the stuff of which thought is made."

The Neuroscience of Deep Work

What's happening in our brains when we attempt to work deeply in a shallow environment?

When you switch from one task to another, your brain doesn't immediately follow. Instead, a phenomenon known as "attention residue" occurs where part of your attention remains stuck on the previous task. Studies show it takes an average of 23 minutes to fully refocus after a distraction.

Meanwhile, deep work activates a neural network called the "default mode network" (DMN), which enables the brain to make novel connections between ideas—leading to insights and creative breakthroughs that aren't possible during fragmented attention.

Perhaps most concerning, research from neuroscientist Michael Merzenich suggests our brains are being "rewired" by constant distraction. The neural pathways that support sustained attention are weakening, while those that respond to novel stimuli are strengthening.

We are literally training our brains to be distracted.

The Deep Work Paradox

Here's where things get fascinating. As Newport points out, we're facing a deep work paradox:

"Deep work is becoming increasingly valuable in our economy at the same time that it's becoming increasingly rare."

This creates a tremendous opportunity. If you can cultivate this skill while others are losing it, you gain a significant competitive advantage. The ability to work deeply is becoming a key differentiator in almost every knowledge field.

It's like weight training in a world where everyone else is getting weaker. The gap between the focused and the distracted grows larger every year.

Five Strategies for Reclaiming Deep Work

After my three-hour experiment, I've spent the past few weeks implementing various deep work strategies. Here are the five approaches that have proven most effective:

1. Schedule Depth Like It's Sacred

My most significant change was moving from "hoping" to find time for deep work to scheduling it like any other important commitment. I now block 90-minute deep work sessions on my calendar each morning, treating them as non-negotiable appointments with myself.

The key: deep work must be scheduled in advance, not squeezed into the cracks of a reactive day.

2. Create Physical and Digital Boundaries

Deep work requires not just mental but physical separation from distraction. I've created a specific deep work environment by:

- Using a dedicated physical space (even just a specific chair can work)

- Employing physical signals (a specific notebook only used for deep work)

- Creating digital boundaries (all notifications disabled, phone in another room)

- Using website blockers during deep work sessions

3. Train the Deep Work Muscle

Like physical fitness, deep work capacity must be built gradually. I started with 45-minute sessions and worked up to 90 minutes over several weeks. Now I'm experimenting with extending to 2-hour blocks.

The critical insight: deep focus is a skill that can atrophy but also be strengthened through deliberate practice.

4. Embrace Productive Meditation

One surprising technique from Newport's work is "productive meditation"—taking a physical activity like walking and focusing your attention on a single professional problem.

I've found that a 30-minute walk while thinking about just one work challenge often yields better solutions than hours at my computer with fragmented attention.

5. Implement a Shutdown Ritual

Perhaps counterintuitively, the ability to work deeply relies on the ability to fully disconnect. I've adopted an end-of-day ritual where I review open tasks, plan the next day, and then completely disconnect from work with a specific phrase: "Shutdown complete."

This practice acknowledges that we need mental rest to perform at cognitive peaks.

The Philosophical Dimension

There's something deeper happening here beyond productivity. The ability to direct our attention is fundamentally connected to our autonomy as human beings.

As neuroscientist Adam Gazzaley explains: "If we're not able to manage our attention, we are not able to manage our lives."

In a profound sense, the quality of your life emerges from the quality of your focus. What you pay attention to becomes your lived experience. If your attention is constantly fragmented, your experience of life itself becomes fragmented.

Nineteenth-century psychologist William James recognized this when he wrote: "My experience is what I agree to attend to."

The Deep Work Revolution

I believe we're approaching an inflection point similar to what happened with physical fitness in the mid-20th century. Until the 1960s, most Americans didn't exercise deliberately. Now we recognize physical exercise as essential for health.

I predict a similar revolution with cognitive fitness. As the costs of chronic distraction become clearer, more people will recognize the necessity of deep work practices for mental health and cognitive performance.

Those who develop this capacity early will have an enormous advantage—not just professionally, but in their ability to live meaningful, directed lives in an age of distraction.

The Challenge

I'd like to end with a challenge: try your own deep work experiment. Start with just 90 minutes of genuinely undistracted focus on your most important work. Notice not just what you accomplish, but how the experience differs from your normal workday.

Then ask yourself: What would be possible if this became your normal way of working rather than a rare exception?

I suspect the answer might change how you structure your entire professional life.

What has been your experience with deep work? Have you found techniques that help you maintain focus in our distraction-rich environment? I'd love to hear your thoughts in the comments.